In this post, I continue the draft of sections of my forthcoming book, “Marxian Economics: An Introduction.” The first five posts (here, here, here, here, and here) will serve as the basis for Chapter 1, Marxian Economics Today. The next six (here, here, here, here, here, and here) are for Chapter 2, Marxian Economics Versus Mainstream Economics. This post (following on four previous ones, here, here, here, and here) is for Chapter 3, Toward a Critique of Political Economy.

The necessary disclosure: these are merely drafts of sections of the book, some rougher or more preliminary than others. I expect them all to be extensively revised and rewritten when I prepare the final book manuscript.

Finally, because of a contractual commitment (which limits the amount of the draft of the book I am allowed to publish on this blog), this will be the last book-related post for a few months.

Toward Marx’s Critique of Political Economy

There is no necessary trajectory to Marx’s writings, no reason his earlier writings had to lead to or culminate in Capital. However, as we look back from the vantage point of his critique of political economy, we can see the ways his thinking changed and how the elements of that critique emerged.

In this section, we take a quick look at some of Marx’s key texts prior to writing Capital: the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, the Theses on Feuerbach, the German Ideology, the Grundrisse, and A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Together, they will give us a sense of how Marx’s ideas developed over time.

We will also see two themes emerge over the course of these texts: the role of critique and a focus on social context. First, Marx doesn’t start (in these texts or, for that matter, in Capital) with a given approach or set of first principles. Instead, his method is to engage with ideas and problems that were “out there,” in the intellectual and social worlds he inhabited, and to formulate a critique, thereby giving rise to new ways of posing issues and answering questions. Second, Marx’s concern is always with social and historical specificity, as against looking for or finding what others would consider to be given and universal. Thus, for example, Marx eschews any notion of a transhistorical or transcultural “human nature.” Instead, in his view, different human natures are both the condition and consequence of particular social and historical circumstances. Much the same holds for his method of engaging economic issues.

Once Marx left Germany and found his way to Paris, he met Engels for the first time (thus initiating, following on their previous correspondence, a life-long collaboration) and also began what he considered to be a “conscientious critical study of political economy,” the mainstream economics of his day. The result was a series of three manuscripts (often referred to as the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 or the Paris Manuscripts, which were written between April and August 1844 but only finally published, to considerable interest, in 1932).* What readers will find in the manuscripts is, having “proceeded from the premises of political economy” (meaning “its language and laws,” the assumption of “private property, the separation of labor, capital and land, and of wages, profit of capital and rent of land,” and so on), Marx arrives at conclusions and formulates new terms that run directly counter to those of Smith, Ricardo, and the other classical political economists. In particular, Marx argues that, under capitalism, as workers become reduced to commodities, what they produce confronts them as “something alien.” Therefore, their labor (using terms borrowed from Feuerbach’s critique of Hegel) becomes “alienated” or “estranged.”

it is clear that the more the worker spends himself, the more powerful becomes the alien world of objects which he creates over and against himself, the poorer he himself–his inner world–becomes, the less belongs to him as his own. It is the same in religion. The more man puts into God, the less he retains in himself. The worker puts his life into the object; but now his life no longer belongs to him but to the object. Hence, the greater this activity, the more the worker lacks objects. Whatever the product of his labor is, he is not.

He then demonstrates that the taken-for-granted assumptions of classical political economy—private property, wages, and so on—are themselves the products of estranged labor. Thus, the distinctions made by the mainstream economists of Marx’s time—between profit and rent, between both and wages, and so on—are rooted not in the nature of things, but in particular social and historical circumstances. They are, in other words, peculiar to capitalism.**

As we saw in a previous section, Marx then (in 1845) developed a critique of Feuerbach. Over the course of his eleven short theses, Marx rejects the idea of a single anthropology (the “essence of man” or human nature) and focuses, instead, on the ensemble of “social relations,” the “historical process,” and “social humanity.” The result is social practice, that is, the goal of not just interpreting the world, but of changing it.

The next year, Marx coauthored with Engels a long set of manuscripts (like the 1844 manuscripts, only published in 1932) in which they challenge the one-sided criticisms of Hegel by Bruno Bauer, other Young Hegelians, and the post-Hegelian philosopher Max Stirner. There, in their attack on German philosophy for having been obsessed with religion (and therefore self-consciousness or the realm of ideas), Marx and Engels announce for the first time what they call the “materialist conception of history,” with an alternative starting-point: “real individuals, their activity and the material conditions under which they live, both those which they find already existing and those produced by their activity.” This focus on social production means Marx and Engels can transform consciousness itself into a “social product,” which develops historically and changes according to particular forms of society or social relationships.***

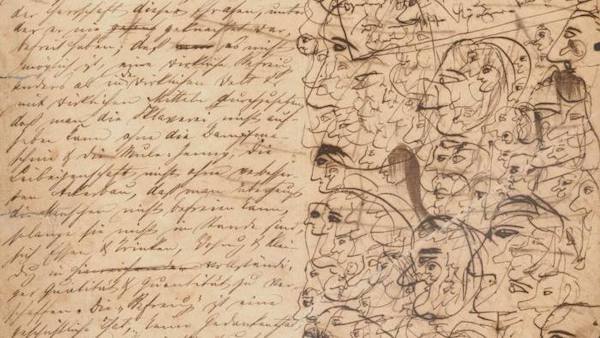

Later, once Marx had settled in London, he spent much of his time in the British Museum (a national public museum, which contained both natural history objects and a massive library) studying the texts of the classical political economists. The result were a set of notebooks, called the Grundrisse (literally outlines or plans), which are often considered to be first draft of Capital.**** While the topics Marx covered are wide-ranging, from value and labor to precapitalist forms of economic and social organization and the preconditions for communism, what is of interest here is his announcement of where he thinks the critique of political economy should start: with “socially determined individual production.”

Why is this important? Because it represents Marx’s break from the notion of natural production, and therefore from the mainstream economics of his day (as of our own). In classical political economy (as in neoclassical economics), capitalism and other economies are considered to be natural, because they are finally reduced to and can be explained by certain given or exogenous factors, such as population, technology, and resources (to which neoclassical economists add given preferences). Also, they take individuals as their point of departure (the most famous example being Robinson Crusoe, a story that is repeated even today in mainstream economic textbooks).

Marx’s alternative view is that economics should start with social individuals, “individuals producing in society,” not given individuals outside of particular historical and social contexts. Moreover, the focus should be on “social production”—different, socially determined ways of producing goods and services—not on any kind of production in general (which students today will recognize in the technical apparatus of isocost and isoquant curves).

Marx also demonstrates his debt to Hegel, in discussing the relationship among production, distribution, exchange, and consumption. Where the classical political economists posit that the goal of production is consumption, and many of the critics worry about distribution, Marx sees them in terms of a “dialectical unity.” In its most general form,

A definite production thus determines a definite consumption, distribution and exchange as well as definite relations between these different moments. Admittedly, however, in its one-sided form, production is itself determined by the other moments.

It’s a distinction that shows up today in the debate about distribution (through free markets) versusu redistribution (through government programs). What the participants in that debate forget about is the initial distribution related to production (and all that entails for consumption, distribution, and exchange), that is, society produces itself through its initial distribution. It’s that initial distribution that is taken as given in mainstream economics, then as now.

Marx also announces his break from existing ways of carrying out economic analysis, whether starting from abstract first principles (and deducing the rules that govern reality) or from empirical reality (whereby certain “laws” are extracted). Instead, he argues, the method he proposes is a movement from the abstract to the concrete. In other words, economic analysis is itself a process of production—one that starts from relatively abstract notions and, adding more and more determinations or circumstances, arrives at a relatively concrete notion (“the way in which thought appropriates the concrete, [which] reproduces it as the concrete in the mind”). It is not a question of bridging the gap between thought and reality (in terms of some kind of validity criterion) but of producing within thought a particular conception of economic and social reality. The implication, of course, is that different economic theories will lead to different, incommensurable conceptions of capitalism and other economic systems.

Finally, in 1859, Marx published A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. There, he designates his break from the philosophies of both Hegel and Feuerbach with what has become one of his most famous expressions:

It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.

This is Marx’s critique of both Hegel’s notion of the Absolute Spirit and of Feuerbach’s alienated consciousness. It’s not an issue of individual consciousness or virtue within existing social order but the conflict-ridden social order itself. Another way of putting this in terms of contemporary debates is: you can’t just have a semblance of freedom (which often means blaming the victims) but you need real freedom, that is, economic and social change that makes the exercise of freedom possible. It’s the same idea that has motivated many working-class political movements, from the nineteenth century onwards, which have demanded an end to poverty and access to decent housing, healthcare, and so on for the majority of people by identifying and seeking to eliminate the economic obstacles to what they consider to be fundamental human rights.

Marx then appends a quotation from Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, which can also serve as a warning to readers as we embark, starting in the next chapter, on a detailed study of Marx’s critique of political economy:

Qui si convien lasciare ogni sospetto

Ogni vilta convien che qui sia morta.*****

———

*The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 was first published in Germany by the Institute of Marxism-Leninism in Moscow in 1932, in the language of the original. In English, this work first appeared in 1959, published by the Foreign Languages Publishing House in Moscow, translated by Martin Milligan.

**Marx also presents in those manuscripts his critique of “piecemeal social reformers,” including the French socialist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, “who either want to raise wages and in this way to improve the situation of the working class, or regard equality of wages,” for not going far enough, because they accept the existence of private property and estranged labor. In this sense, they want to improve, but not eliminate and move beyond, capitalism. And, in the third manuscript, Marx credits Hegel with understanding the importance of labor as the source of alienation; but then criticizes Hegelian philosophy for focusing entirely on “abstractly mental labor” (as a question only of “self-consciousness”) and therefore overlooks (just like the classical political economists) economic and political alienation.

***They also announce what, at least at this stage, what they mean by “communism”: “not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the premises now in existence.”

****The seven notebooks were written during the winter of 1857–58 but were only published in 1939. The first English-language translation (by Martin Nicolaus) appeared in 1973. The publication of the Grundrisse was important not only for readers of Capital (and much discussion has ensued about the overlaps and differences between the two), but also for other fields, especially for the new field of cultural studies (in the work of, among others, Stuart Hall and the famous Center for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham).

*****The lines are from Canto III of “Inferno” (as Virgil’s reply to Dante, who has just read the inscription over the Gates of Hell). The translation is: “Here one must leave behind all hesitation; here every cowardice must meet its death.”